Some time has passed now since the first set of banking news flow hit our screens and we have been closely monitoring the evolving situation. Within the space of two months, we have seen four US bank failures, First Republic, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank and Silvergate Bank. This has resulted in the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in US history. Across the pond, closer to home, Switzerland’s second largest bank, a 167-year-old institution, Credit Suisse fell victim, resulting in the acquisition by UBS assisted by the Swiss National Bank (SNB).

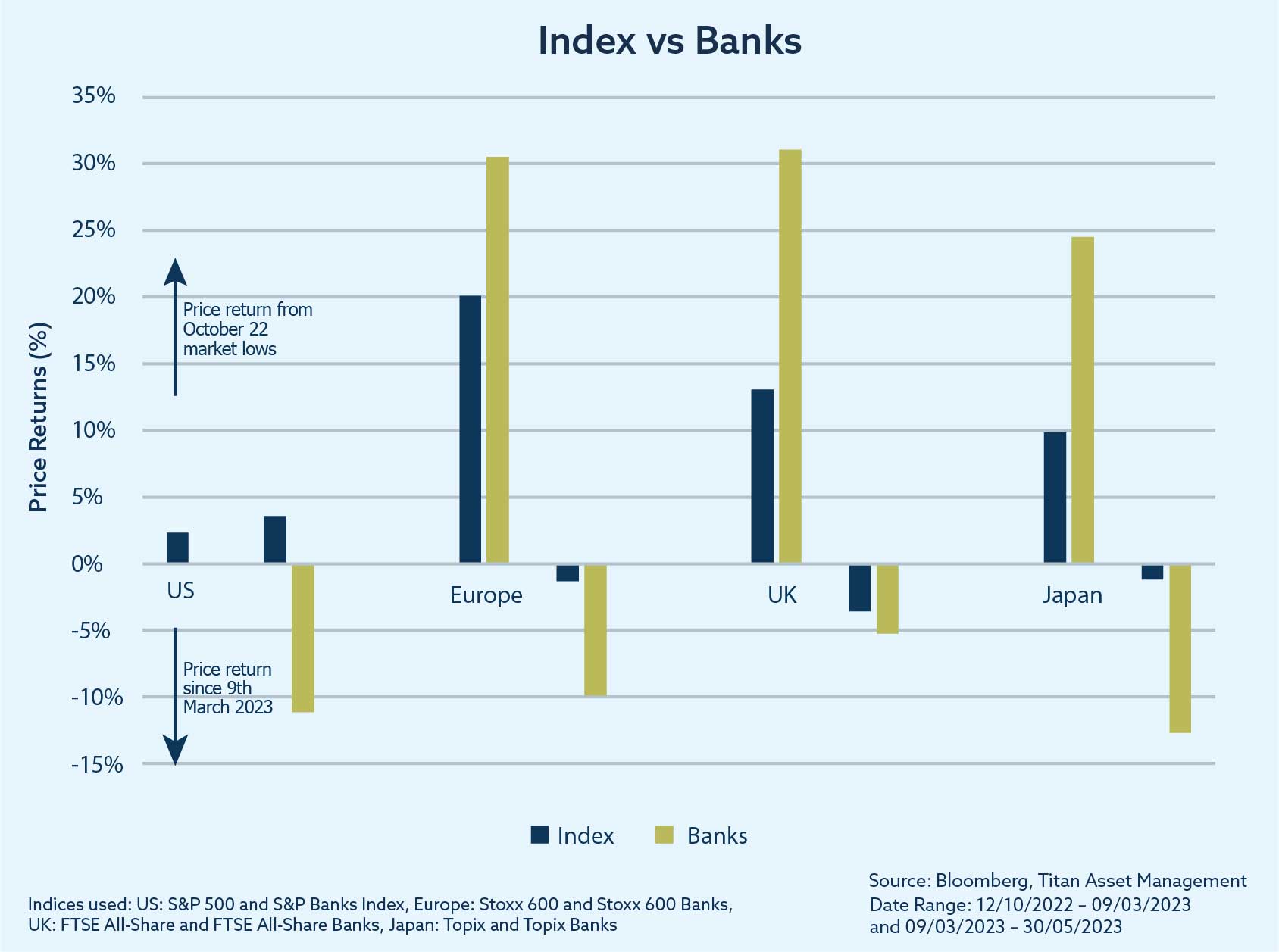

We have not held any direct banks/financials ETFs or funds within our portfolios and have been underweight the sector for some time now. This has been predicated on our view that the lagged effects of unprecedented global monetary tightening have yet to fully feed through into the real economy and the market has not been pricing this in. We were reluctant to chase the cyclical rally led by financials that kicked off the year and while valuations have compressed significantly since March, we would not look to add exposure until some of the cyclical headwinds abate.

A recap of the banking events

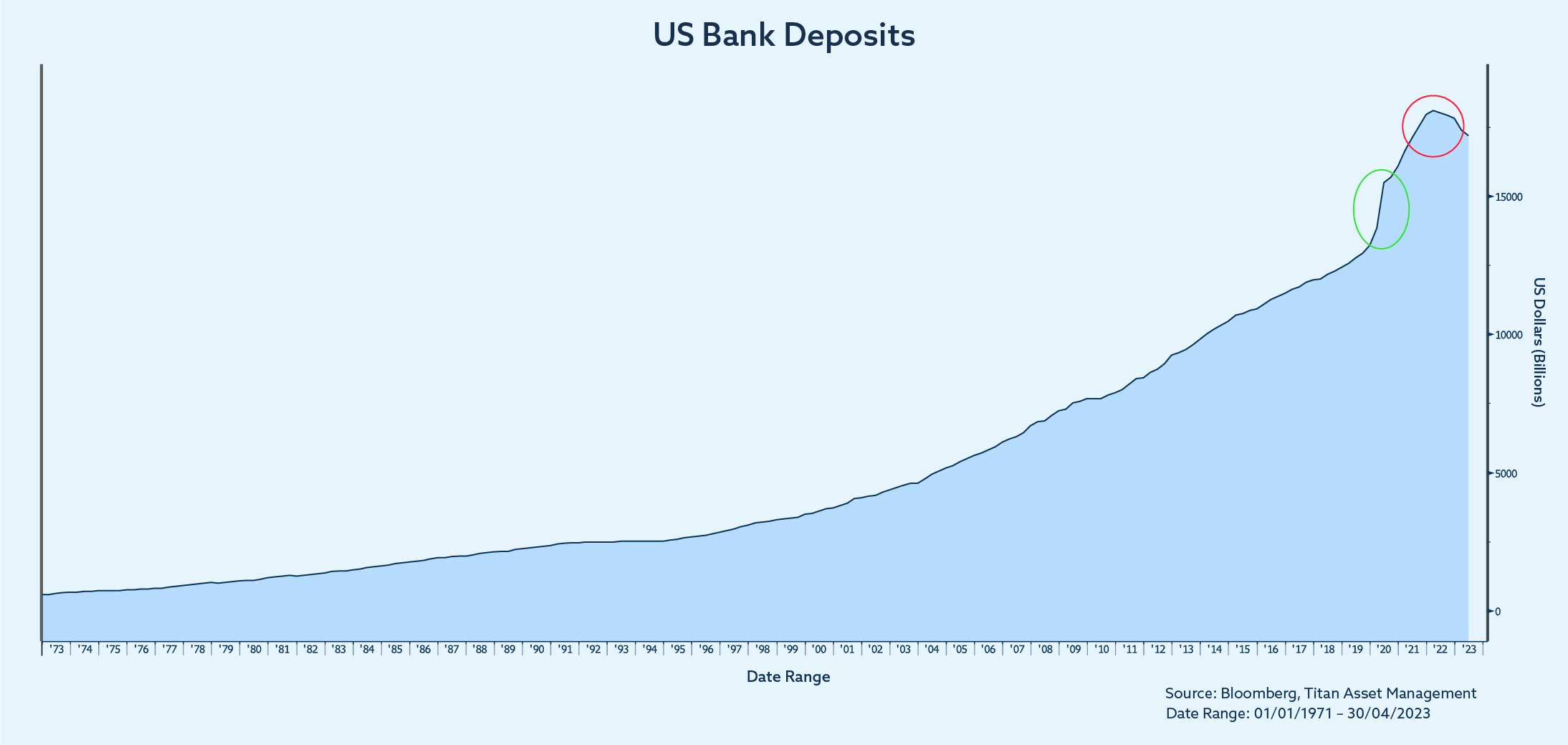

While many of the structural issues faced by these failed banks were idiosyncratic in nature, the seismic shift in interest rates over the past year has undoubtedly augmented these fragilities, particularly in the case of the US regional banks. SVB is a prime example as the central bank liquidity tidal wave during the pandemic meant their client base of predominantly venture capital-backed tech start-ups were awash with cash.

This led to the bank’s deposit base almost trebling in three years, far outstripping loan growth. Rather than hold the excess liquidity in cash, many US regional banks opted to invest in the bond market with SVB leading the charge, holding 57% of its assets in bonds by the end of 2022.

As interest rates rose, fixed income markets fell causing an estimated $620bn of unrealised losses on bond portfolios across the US banking system at the end of last year. Unrealised losses became realised losses for the likes of SVB and co as their clientele of easy-money beneficiaries lost this tailwind and began to withdraw cash.

Higher rates also meant higher-yielding money market funds became attractive alternatives to bank deposits. Consequently, last year was the first year since 1948 that deposits in US commercial banks fell according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

The speed at which deposits left the system was unprecedented as the digitalised age of internet banking and social media posed a new factor driving the velocity of withdrawals; this was exacerbated by the concentration of some of the banks’ client bases. US regional banks lost over $100bn of deposits in one week in March.

After SVB, Signature Bank and Silvergate Bank all failed in March, First Republic took over SVB as the second largest US bank failure less than two months later, also succumbing to significant held-to-maturity losses, deposit flight and deteriorating shareholder confidence (the share price declined 75% in two weeks).

JP Morgan acquired the firm, making it the buyer of the two largest failed US banks. Supporters of the deal would argue Mr Dimon was the white knight coming to the rescue and minimising banking disruption while others protest the behemoth already “too big to fail” is only gaining further market share via this deal.

Credit Suisse had its own unique set of problems, suffering from several high-profile scandals in recent years (money laundering issues, corruption, spying, Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital collapses). Senior management attrition, restructuring attempts and the finding of ‘material weakness’ in its annual report all drained investor confidence, ultimately resulting in the firm’s demise.

Market reaction

Banks’ stocks globally suffered losses, at one point, wiping over $450bn in market cap in just two days, greater than the $312bn lost in the worst three days of the financial crisis. The index of global banking stocks fell over 12% in March, since recouping some of its losses while the US Regional Banks Index was worse hit, down over 30% from its highs earlier in the year.

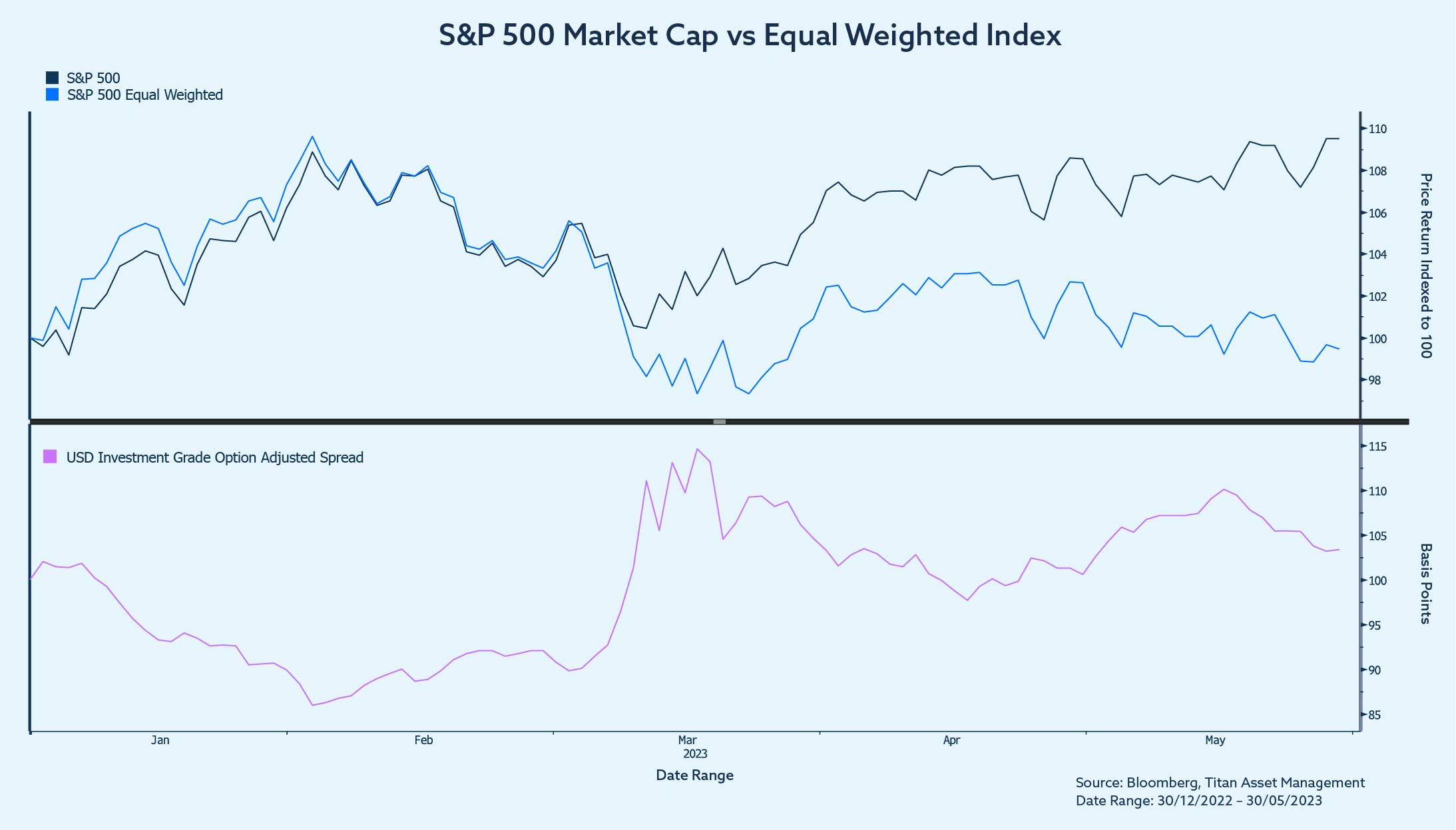

Some interesting dynamics have played out since March’s banking fallout underneath the headline equity market moves at the index and sector level. Market breadth has narrowed significantly, particularly in the US as highlighted by the chart below. The S&P 500 market cap index closely tracked its equal-weighted counterpart for the year until the banking news unraveled which has since led to around an 8% outperformance in under three months.

Absolute Strategy Research estimate that eight mega-cap stocks are accountable for almost all the S&P 500’s gains year-to-date. Wider credit spreads triggered by banking stress have favoured net cash-positive companies with longer maturity debt such as some of the tech heavyweights.

The market’s aggressive repricing of interest rate expectations downwards with an eye to prioritising banking stability has also been a tailwind for the tech sector. Apple and Microsoft have added over $1 trillion in market cap this year with Apple’s market cap alone now eclipsing the Russell 2000 and the FTSE All-Share individually.

Blue line: S&P 500, white line: S&P 500 Equal Weight, red line: US Investment Grade All Sector Option Adjusted Spread Top Y axis: price return, bottom y axis: Spread (basis points)

It has been a contrasting picture for banks relative to tech but one of the few bright spots in the banking sphere has been First Citizens BancShares which has rallied over 150% from its March lows after acquiring the majority of SVB’s assets. The SVB deal led to the company reporting a 3000% jump in profits last quarter.

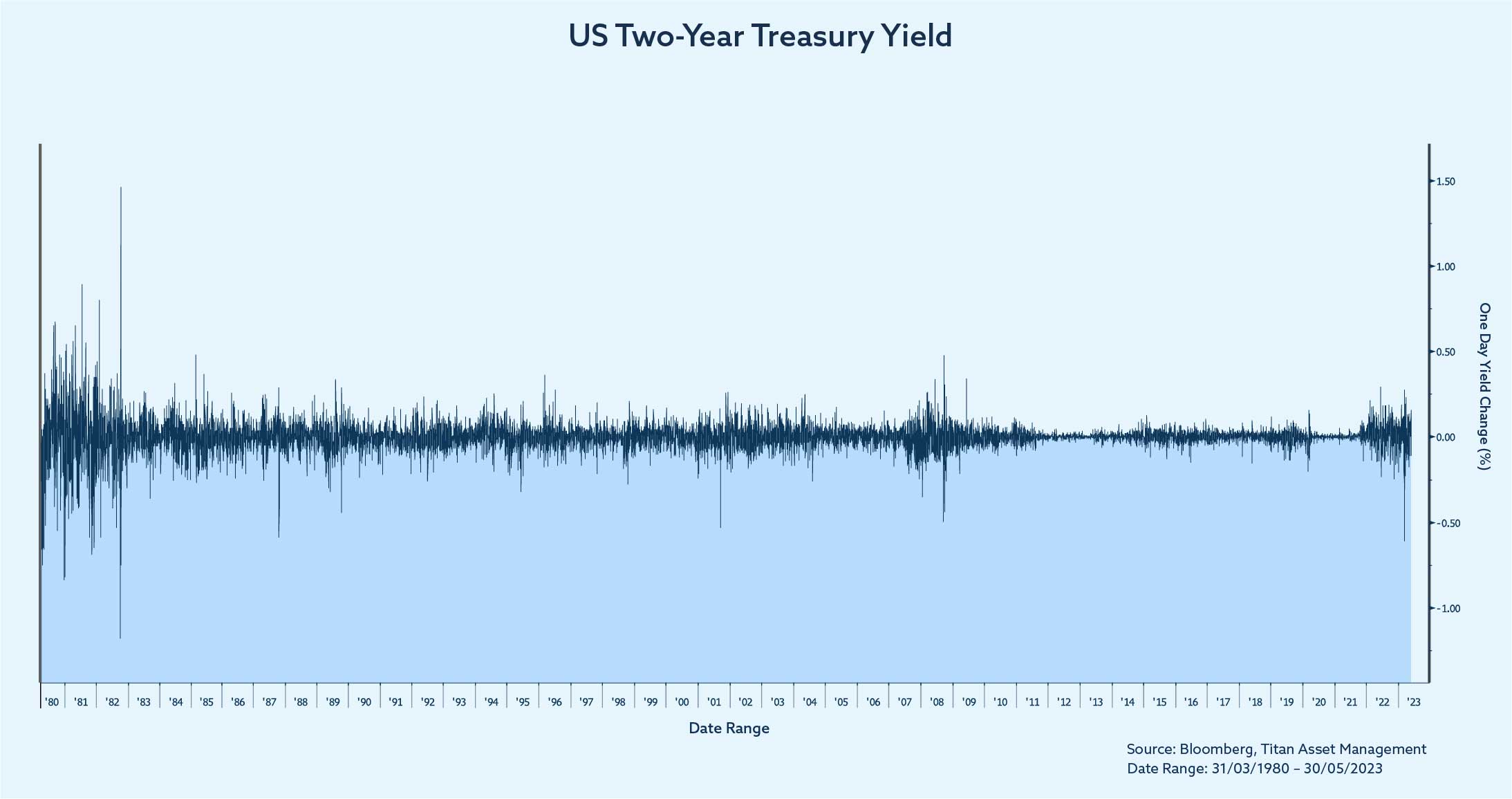

The immediate bond market reaction to the initial banking fallout was more extreme than the equity market, viewing the situation through a more pessimistic lens. The US 2-Year Treasury had its largest one-day drop in yield since the early 1980s as traders rapidly repriced the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy stance to focus on financial stability through rate cuts.

The MOVE Index, a measure of US Treasury market volatility has retreated after hitting its highest level since 2008 in March following the three regional bank failures. It is evident that the bond market will likely react first with a more cautionary stance relative to the equities to any further signs of banking stress which is more aligned with our defensive positioning.

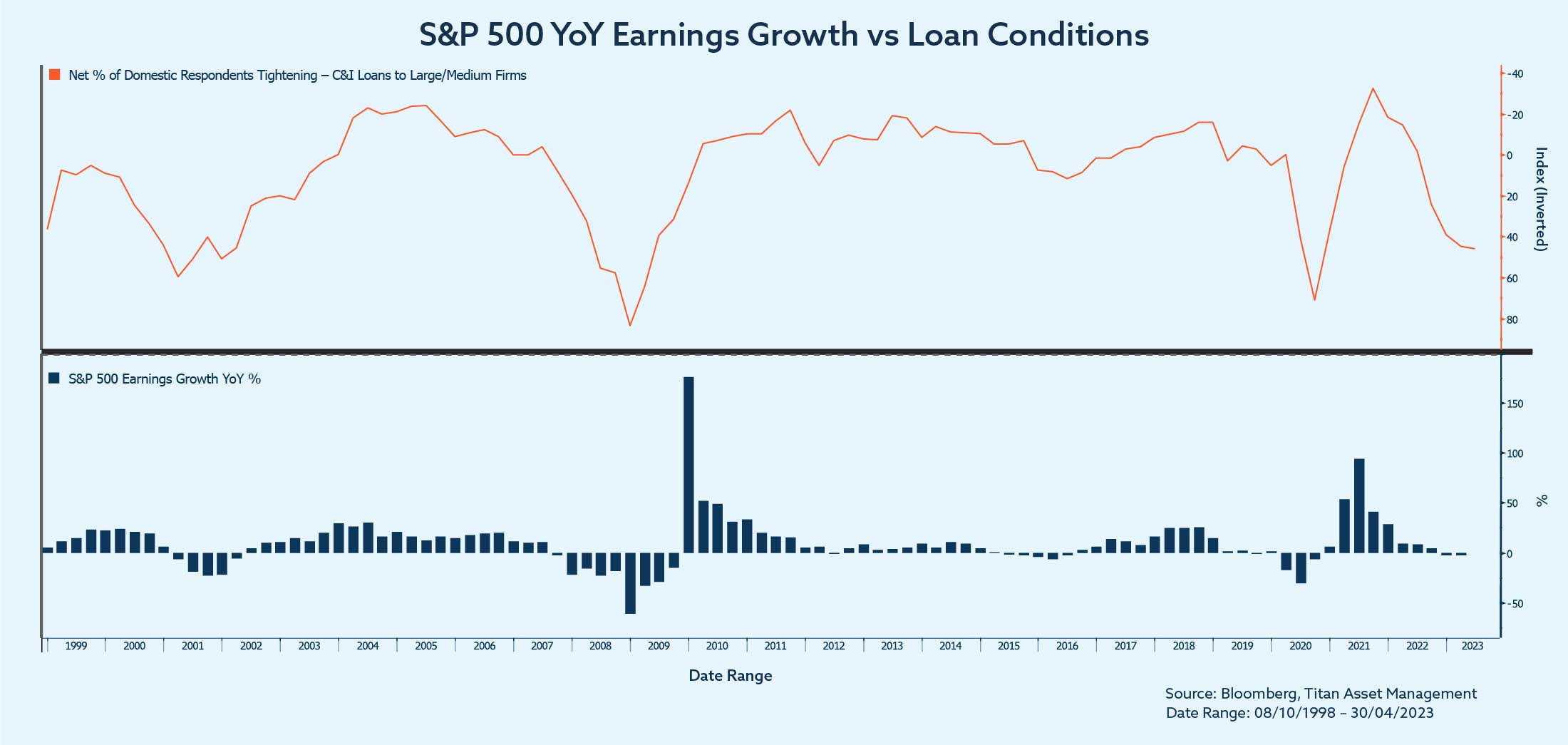

Lending standards have been tightening for over a year now prior to any bank failures which have since accelerated and are set to continue. This has been the largest magnitude of credit tightening since the global financial crisis with the amount of corporate debt trading at distressed levels up around 300% over a year.

Tightening lending conditions typically lead to slowing economic growth and the chart below highlights the strong historic relationship with earnings. Analysts may be prematurely looking to trough earnings with a strong rebound without factoring in the effects of a weakening loan environment.

Will we see a full-blown banking crisis?

We think it is unlikely we see systemic contagion that results in a credit crisis akin to 2008. Banks are far better capitalised with much stronger liquidity profiles post-financial crisis. This is particularly the case in Europe where core tier-one capital ratios are roughly double what they were in 2008.

Central banks and regulators have been swift to react by protecting depositors of the failing banks and providing funding facilities to ease liquidity concerns. Both the Bank of England and European Central Bank reassured investors that the Additional Tier One (AT1) bondholders do rank ahead of equity holders in priority to claims, stating that the Credit Suisse AT1 write-down was unique to Swiss regulation (subject to ongoing litigation).

US regulators are likely to look to their peers in Europe and become stricter with regional banks as they are currently deemed too small for certain regulation. European legislation requires banks of all sizes to include unrealised mark-to-market losses on Available-for-Sale portfolios in Core Tier One calculations whereas banks in the US with under $250bn in assets are not subject to this.

Similarly, “smaller” banks in the US face less strict liquidity coverage ratios compared to European banks. Tightening these forms of regulation for US regional banks will help prevent similar banking issues to the ones over the last few months. Bank stress tests globally may need adapting to cover more sources of contagion risk such as the concentration of client bases and technology’s impact on deposit flight. The events over the last few months may also lead to corporates and individuals rethinking how diversified their deposit channels are.

Closing remarks

The recent banking failures was a stark reminder to depositors and investors that we are not immune from bank runs despite the tightening of regulation since the great financial crisis. Confidence is a vital component to the health of the banking system that cannot be found on the balance sheet and the recent banking episodes shows how quickly confidence can be lost.

The size, breadth and speed of monetary tightening from a decade of record-low rates will challenge the financial system and these collapses are partially a symptom of this. Central banks must now contend with the fine balancing act between lower inflation, avoiding an economic contraction alongside banking stability added to the mix.

While for the most part, banks globally are trading at low price-to-book multiples relative to history, we believe this is for good reason given the macroeconomic environment even if further failures are avoided.

Sekar Indran