Turning Nuclear

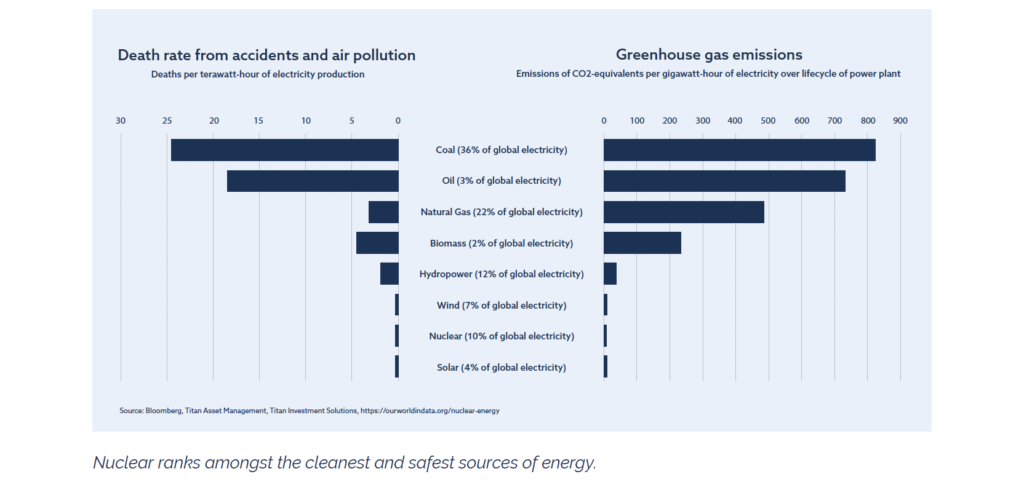

Nuclear energy is at a tipping point. Following years in the wilderness there is growing enthusiasm around nuclear power as a pragmatic way to solve the world’s growing energy needs whilst striving to achieve net zero emission ambitions. Alternative energy sources including wind and solar power offer compelling sources of clean energy, but the storage and transmission of energy produced is currently less reliable than the consistent base-load output nuclear power delivers. With almost $4 trillion of renewable energy investment over the last ten years the reliance on fossil fuels has barely shifted, falling just 1% as a portion of global energy consumption. Meanwhile, nuclear energy represents just

10% of global electricity production. Importantly, nuclear power is one of the safest and cleanest sources of energy available.

The nuclear resurgence story hit the headlines last week as nations gathered at the annual climate change conference, COP28. The US announced a pledge to triple nuclear power by 2050. Signatories included current users of nuclear energy including the UK, France, Romania, Sweden, UAE, Japan and South Korea as well as newcomers such as Poland, Ghana and Morocco. The tide of public opinion seems to be turning. In the US

state of Illinois, the governor recently signed a bill lifting a 35 year plus ban on new nuclear reactors, whilst a Sky News Poll found 4 out of 5 Australians favoured ending the moratorium on the use of nuclear power in the country.

Energy demand will continue to rise, catalysed further by the adoption of AI technology. Strong government-backed demand from energy utility companies will drive the price of uranium, a key ingredient for producing nuclear power, notably higher over the coming years.

The World Nuclear Association (WNA) recently released its updated report for November 2023. It highlights 62 new reactors under construction globally and estimates that 26 will come on-line by the end of 2025 and a further 21 new reactors to start-up by 2026/2027. New nuclear reactors require 3 years worth of fuel prior to start-up. Those operators will need to order mined uranium now so that it can be converted, enriched and fabricated by the projected start-up date. There is a lot of demand in the pipeline with China leading the charge on new plants under construction. Importantly, utility buyers are price inelastic in that their ultimate goal is to source uranium to power the nuclear power plant. There is no substitute to uranium and the contribution to total running cost is relatively low. There is also growing enthusiasm over small modular rectors (SMR’s) which harness new technology to provide a typically smaller source of portable energy that mitigates against cost overruns which many larger reactors suffer from. Earlier this year Microsoft put out a job vacancy for a candidate to roll out its new SMR program whilst in the UK Rolls-Royce is among six firms shortlisted for SMR development.

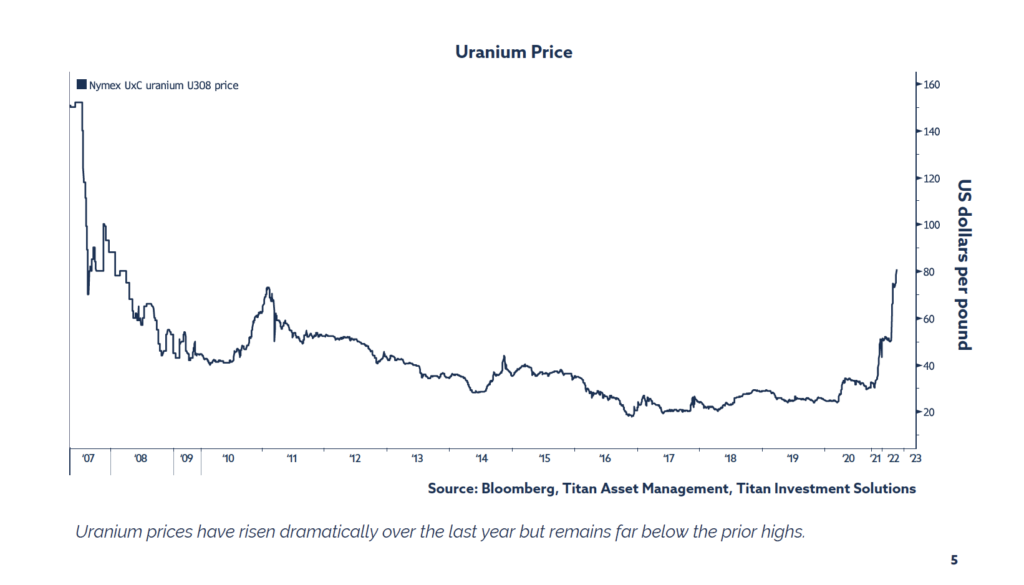

Meanwhile, there is a meaningful supply deficit. The prior supply glut, following the Fukushima disaster and subsequent German retrenchment, is in the rear-view mirror. Over the years utility companies had relied on abundant inventories and cheap prices which created complacency, the effects of which are only now coming to light. With minimal available supply in the spot market, most transactions take place via a request for proposal (RFP) in the term market, for future delivery. Even here there are signs of stress as the lack of exploration and long lead times exacerbate the supply-demand deficit which is forecast to continue over the coming years. We have seen signs of just how tight the market is via recent orders for small quantities of uranium which has driven the price notably higher.

For example, November has seen a 10% jump in the spot uranium price on the lowest monthly trading volume in 18 months. Anecdotally, South Korea’s nuclear utility, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power, asked producers to make offers to supply them with a much larger quantity, over six million pounds of Uranium, over 5 years from 2026 to 2030 with terms including $58 a pound floor price/$90 ceiling on the spot priced portion. Whilst many transactions are subject to non-disclosure agreements, the understanding is they received no offers due to the unattractive terms presented. That would not have been the case a few months ago. Contracts no longer include flexibility over quantities supplied and the evidence suggests the market is incredibly tight and the price will need to rise substantially from here. We are aware of around 10 RFPs in the pipeline with more to come. Uncovered reactor demand and our scepticism over any meaningful supply response any time soon means the trend of rising prices is here to stay.

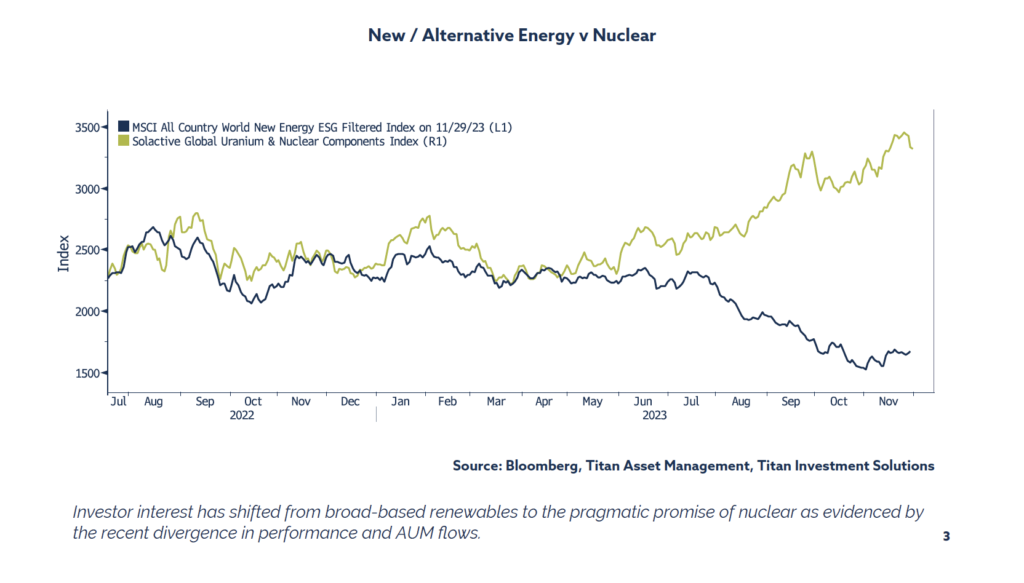

Then there is the financial angle. Demand will be turbo-charged by growing investor appetite for uranium from retail players and financial institutions alike. Generalist investors are slowly turning to this niche sector as evidenced by the growing number of ETFs providing exposure to uranium miners and companies in the nuclear industry. ETF assets under management have increased by a multiple of twenty over the last 3 years alone but remains low in absolute terms. Specialist funds, like the Sprott Uranium Trust are at all time highs with new specialist funds coming to market, set-up to acquire and sequester the commodity from the market. There is also growing interest from key financial players as evidenced by the growing chorus of news stories on uranium across financial data services and publications. The inflow of AUM to this niche and comparatively small sector could have a dramatic impact on price via something known as the fly-wheel effect.

Another factor to consider includes the growing requirement for energy security against a backdrop of escalating geopolitical tensions. To provide an example, the bottle neck in the uranium story is enrichment. Uranium enrichment is the process that is necessary to create an effective nuclear fuel out of mined uranium. Russia currently provides approximately 40% of enriched uranium globally. However, sanctions against Russia, which currently exclude uranium, are set to broaden and there is growing concern that Russia may escalate the ongoing weaponization of energy by pre-emptively cutting supply to western nations.

Kazatomprom, based in Kazakhstan, is the world’s largest producer of natural uranium. The company recently agreed to sell more than 50% of its total book value of assets to China’s State Nuclear Resource Development Company with additional supplies also flowing to Russia, highlighting close geopolitical ties which threatens to leave western nations in the cold. French President Emmanuel Macron recently visited Kazatomprom in an effort to secure a new source of uranium following the recent coup in Niger. Niger supplied 15% of France’s uranium needs and accounts for a fifth of the EU’s total uranium imports. But in a twist of fate, Macron may struggle to secure delivery given the only route to do so, other than Russia, is through Azerbaijan, a country with which he has not enjoyed good diplomatic relations. This example is indicative of the geographical logistical constraints nations face when transporting a highly controlled substance across multiple borders over and above the complex geopolitical backdrop.

To summarise, high demand, driven by pragmatic clean energy aspirations, and growing financial interest in the sector is on a collision course with a long-term structural supply deficit, complex logistics, and escalating geopolitical tensions. We think this will drive the price of uranium meaningfully higher over the coming years. Uranium prices can rise to the prior high, around $150 a pound, or closer to $200 a pound on an inflation adjusted basis. That represents a 2.5x return from current levels. The rise in the price of uranium should also benefit uranium miners and companies operating across the nuclear life cycle. Equities offer leveraged exposure to the underlying commodity, providing an attractive convexity profile and the potential for even greater upside.

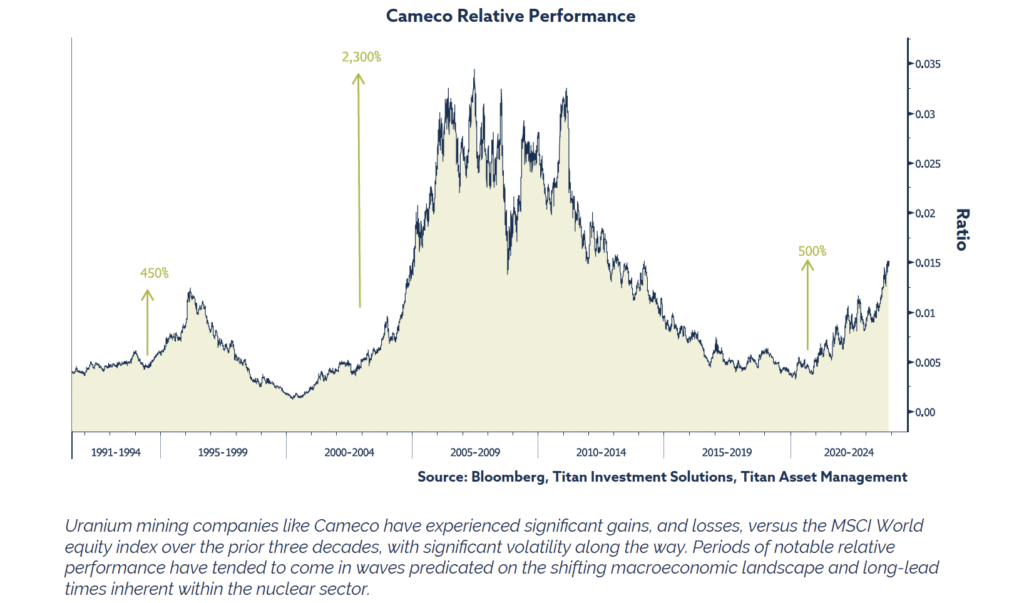

There have been three uranium super-cycles over the last three decades. Using Cameco, one of the world’s largest publicly traded uranium companies, based in Canada, as a large-cap high-quality proxy for the sector, we observe the three periods of strong relative performance. The first, in the mid-1990s saw the stock outperform the MSCI World equity index by approximately 450% priced in UK pounds. The second, which took place in the early 2000’s saw the stock outperform the MSCI World by an astonishing 2,300%. We are currently part way through the third wave, with the share price outperforming by 500% since the 2020 low.

Uranium mining companies like Cameco have experienced significant gains, and losses, versus the MSCI World equity index over the prior three decades, with significant volatility along the way. Periods of notable relative performance have tended to come in waves predicated on the shifting macroeconomic landscape and long-lead times inherent within the nuclear sector.

Whilst the price of uranium has already moved a lot over the last year, we think there is further to run. The fundamental case, and technical set-up for uranium, and the nuclear sector as whole, is better now than at any time over the last three decades.

Both the raw commodity and equities linked to this narrative offer ways to access this highly differentiated sector. Whilst high quality names like Cameco have performed well so far, the majority of companies continue to lag the underlying commodity making this a compelling opportunity to research and invest in the best names.

We currently have exposure to uranium itself and a range of companies involved in the nuclear cycle across our fund range. The sector may experience high levels of volatility and any allocation should be size appropriate and considered within the context of a broader highly diversified portfolio and on a risk appropriate basis.

John Leiper

John Leiper is the Chief Investment Officer of Titan Asset Management and carries direct responsibility for all investments in the Centralised Investment Proposition (CIP) at the firm.

Performance update – March 2022

In my January commentary, the aptly named ‘Bumpy Start’, I concluded by saying that recent events, and extreme market volatility, necessitated a […]